The story of the Amazon we all know (and mostly love) today is an amazing one. Jeff Bezos started the company in June 1994 and called it ‘earth’s biggest bookstore’. However in the first 6 months of its operation, it barely clocked $500k in revenues. But by 1996, it had sales of $16m and in 1997 it sold $148m.

Impressive numbers no doubt but there was a problem behind those numbers – the company was seriously losing money and burning through a frightening amount of cash in the process. By 1999 it was making revenues of $1.6bn but managed to lose $720m on those same revenues. By 2001 its losses had doubled to $1.4bn and it had racked up $2bn in borrowing from banks plus around $8m the initial investors had put into it.

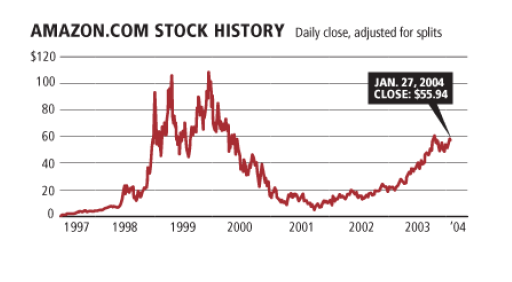

How about its share price after it floated in May 1997 at $18 per share? Have a look at the chart below

Notice the precipitous drop in the share price from a peak of $115 around 1999/2000 to around $5 or so in 2001…all in just over a year. Just imagine you were an investor and you bought at $100…imagine the kind of reports that would have been written by analysts and so on. By 2001 when it made the huge losses referred to above, it sacked 1,300 workers, closed down two of its warehouses and shut down other service centres.

Somehow, in January 2004, ten years after the company started operations, it managed to post its first annual profit of $35m on revenues of around $6bn. Phew! And the rest as they say is history. These days its revenues are around $61bn a year and even though it still makes a loss now and again, it is such a part of the internet fabric that no one panics anymore. The company has almost singlehandedly redefined what the term ‘patient capital’ means. Somehow in all those crazy years when it looked like a lot of money had gone down the drain, Jeff Bezos managed to convince investors and lenders to stick with him.

One of the things that makes America almost unique among capitalist countries are stories like these – the way people will back a company with billions of dollars and stick with it even when it is losing a fortune. Sometimes they don’t even make their money back and the company goes bust along with everything invested into it – a good example was an online grocery delivery company called Webvan that went bust in 2001.

I left Nigeria very early in 2004 and I know definitely that work on The Rock Cathedral had already started. The papers are awash with stories today about the President, Goodluck Jonathan, as well as Tony Blair, former British Prime Minister, opening the now finished church yesterday. The number being touted as the cost of the construction on social media is $85m. It is an impressive building and will sit 14,000 apparently.

Let’s try to walk back 10 years from today. Think of the churchgoers as investors. Pastor Paul Adefarasin sold them a vision and they bought into it. Now if it ended up costing $85m then we can be certain that the initial cost when the idea was floated would have been a fraction of that. Given how inflation can be in Nigeria, let’s say the initial plan was to spend $5m. We can also be certain that Pastor Paul didn’t plan to spend 10 years building the church. I am told that it was originally to be completed in 2000 and was even to be called ‘Millennium Temple’. Selah

When you think about it – ‘investors’ have been pouring money, by way of offerings and building funds, into this project for maybe 15 – 20 years. Let’s say yesterday when it was commissioned was the day it finally turned a profit to complete the picture.

Friends, is the difference between us and the Americans only where we choose to deploy our own patient capital? There’s no doubt about this – we do have patient capital in Nigeria that can nurture a business or project through impossible times till it finally comes good. People were investing their money into this project for years based on no more than the model and 3D images perhaps. I have never been a member of House on The Rock but I can only imagine how many times Pastor Paul would have asked for more money or plans would have changed over the years. Just like Jeff Bezos.

In my head, I like to think of capitalism as a 2-step thing – aggregation and then deployment. First you round-up all the people who have money and find a way to make them give it up (willingly). These can be small sums and is what banks essentially do with your deposits. Aggregation helps you to build up the gunpowder that is capital leading to the deployment stage i.e who do we give it to?

There are 2 clear examples in Nigeria that show we are doing the aggregation part of the equation ok. The first is of course how our churches manage to raise vast sums of money at zero rates of interest just like the $85m above. You only need to go to a Holy Ghost Night programme or a large church in Nigeria to see how capital is being raised from investors on a weekly or monthly basis. Most of the large Pentecostal churches don’t publish accounts so we can only assume billions are raised this way every Sunday.

The other example is our Pension Fund system. Nigeria adopted the Chilean model in 2006 and since then total pension fund assets have grown from $1.8bn to $19bn as at November 2012. We now have 5.3 million Nigerians aggregating around $100m in capital per month into pension funds. And given our population size, there’s potentially plenty more to come.

This is where it all breaks down unfortunately. The deployment stage. In the case of pension funds, most of it still gets lent to government (although that is very slowly changing) and for churches, well buildings get built and other things get bought.

But I know of a very popular business in Lagos that will soon be shut down because it has defaulted on its loan payments. The loans were of course given at circa 20% interest rate and it is now being charged a penalty rate of perhaps another 10% on top of it for having the temerity to default on its payments. And there are plenty businesses like this out there pretty much trying to do the impossible by delivering returns over and above their eye watering cost of borrowing just to stay alive. Yet with a bit more patient capital, some of these small businesses might become world beaters or at least dominate Africa in a decade if they were allowed to grow without banks breathing down their necks. Just imagine if HoTR had taken the funding for the church building from a bank…

These things should challenge us as a country. A lot of countries are richer than us simply because they have figured out a way to direct capital to sectors of the economy that produce the most returns and create the most jobs. It is self-evident that there’s something wrong with the way we are able to finance enterprise in Nigeria. The Omidyar Network recently published an interesting report about Accelerating Entrepreneurship in Africa (read the whole thing if you can). In the section on Nigeria, it said this:

Nigerian respondents cited access to finance as a key challenge for starting and growing small businesses. In particular, the requirements for obtaining capital are prohibitive. As illustrated in Figure A13, Nigeria marginally lags her SSA peers with regard to financing, while the gap to global peers is more pronounced.

In-depth interview participants indicated that collateral of up to 120% is often required for debt financing. As a result, 67% of respondents believe that bank-lending policies for newer companies are more challenging than for well-established firms. There is also a perceived shortage of equity capital with only 15% of respondents believing there is a sufficient supply of equity capital for starting new firms

I highlighted ‘equity capital’ above. This is pretty much another name for patient capital. Not only are we doing much worse than our global peers, we are also alarmingly lagging our peers in Sub-Saharan Africa when it comes to financing enterprise. Surely none of these our peers even globally can match the grandeur of our churches all built with patient capital? The challenge for those of us who want to see enterprise bloom in Nigeria is how to mimic this church model to patiently fund businesses. Should entrepreneurs learn to sell their vision to investors like Pastors? Should we organise overnight investment conferences that somehow convince 50,000 people to attend and then get them to make a contribution before they leave?

Or maybe there’s nothing wrong here and I am just making a mountain out of a molehill. Maybe Nigerians are perfectly rational after all and having considered all the various investment options available to them (and there are legion), they decide to put their money in churches where they are certain of the best returns. Maybe Pastors are the only entrepreneurs that people feel comfortable backing even when things aren’t going to plan. Maybe Pastor Paul is our own Jeff Bezos after all who can convince investors to open their wallets again and again.

In which case, as you were. And I apologise for wasting your time with this post

FF